In the year 1895 a great archaeological discovery shook the British Indian empire. British soldiers had come across a completely intact and preserved Ancient Greek temple in the Chakdara region of what is today Pakistan. A temple which was quickly lost due to the misadventures and loot of British officers.

The tale of the Ionic Temple of Chakdara.

Discovery Of The Temple

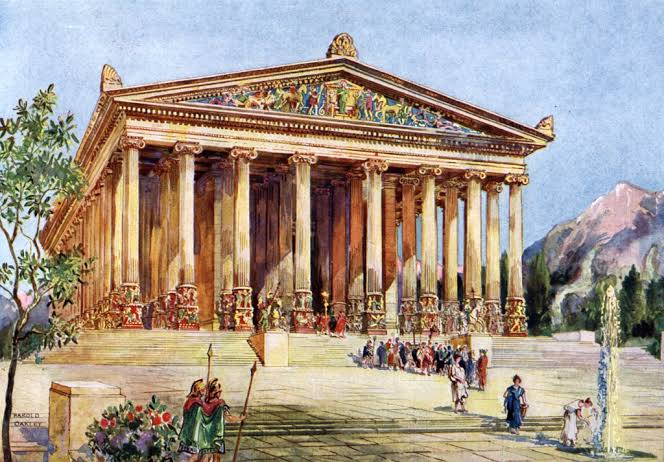

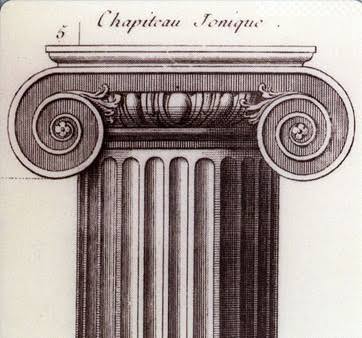

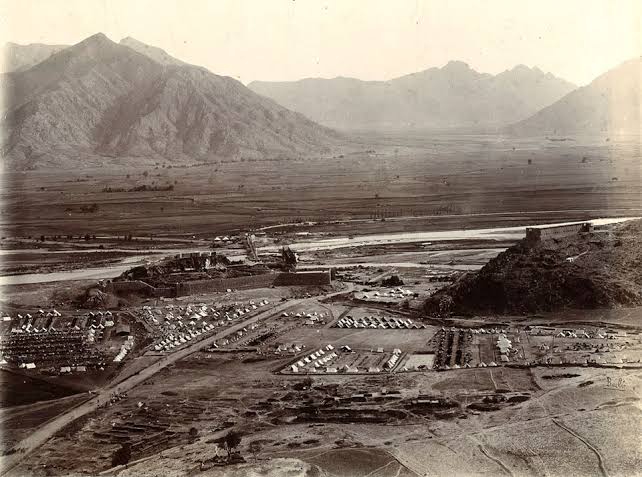

The mountains north of Peshawar valley are known for their archaeological treasures mainly in the Buddhist domain from the days of the peak of Gandhara when an amalgamation of Greek and local culture took place. In such near the town of Chakdara in 1895 there came about a discovery by a British officer of colossal magnitude, a discovery of a temple unlike any other. The officer had noticed that the apart from the Gandharan influences and many smaller details, the temple retained a peculiar quality; actual pillars belonging to the Ionic Order. The Ionic order was one of the 3 principal orders of classic architecture in Ancient Greece and was employed in some of the earliest Ancient Greek temples. This was a quality which distinguished this temple from any other discovered in South Asia.

Account of C.M. Enriquez

In the small account left by this certain British officer named C.M. Enriquez he spoke thus:

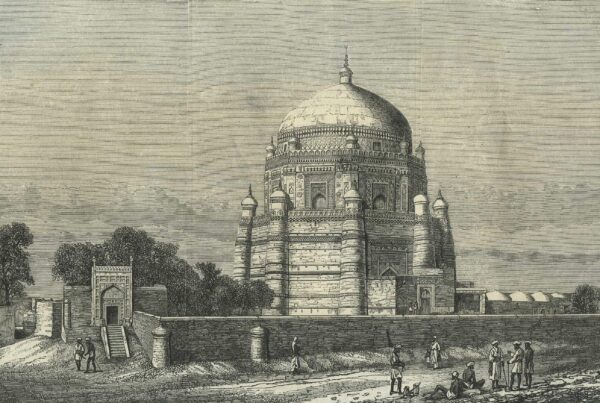

“It was a square building, supporting a hemispherical dome. Two Ionic pillars formed the props to the archway, through which the shrine was entered. The entire porch and the pillars have been removed to the British Museum. In this temple were found Greek lamps, and two statues, the one of Greek dancing girl, and the other of a Greek soldier fully armed. An important find on one of the Topes was a frieze, illustrating the life of Buddha.”

From Enriquez’ account we know of two important things: The temple’s structure, it’s central façade bearing the ionic columns and the dome of the temple were well preserved upon discovery and that the entire front porch and pillars of temple were stolen and handed over to the British museum.

The Visit of Alexander Caddy

As the news of the temple and other sites of interest reached British India, in 1896 Alexander Caddy was dispatched from Calcutta to survey the area. The temple that he was escorted to, as he soon discovered, had been excavated and possibly looted by the same two British officers who were escorting him to it.

A portion of Caddy’s account of the temple read:

“It is a small Ionic temple in antis, the bases and portions of the two columns remaining, while the porch and the capitals of the pillars were wanting and the spring of the dome is open to the sky.”

Both the report of the temple given by Caddy and the photographs of it by taken by him tell us that by the time he had reached it, the temple had lost both its porch and dome and had undergone extremely careless excavations by the officers. It is not known just what amount of Gandharan artefacts had been taken by the officers but it is known that one of them had on multiple occasion sold some of those to the British museum. In 1895 alone more than 300 Gandharan antiquities had been shifted from the Malakand region to the city of Calcutta, on the other end of the colony.

So obscurely lost was everything in connection to the temple that even the report of Caddy was considered perpetually as lost as the temple itself. It wasn’t until Luca Oliveri found a copy of his report in the archives of fort of Malakand which he later published in his book in 2015 did a more detailed account of the temple come about. Through this remaining report and the photos taken by Alexander Caddy, Kurt Behrendt was able to recreate the architectural plan of the temple to the best of his capabilities.

According to Behrendt the main body of the temple consisted of a small cubical cell. It contained a small portico where on the outer façade were located two columns which bore ionic capitals on their upper portions and led into the temple. Another very interesting thing mentioned by Caddy was the presence of stucco birds on top of the main doorway. These birds which he described to be in the form of an owl with outstretched wings was compared to the famous stupa of the double headed eagle from Sirkap in Punjab. Apart from these, many other details of the structure and architecture of the temple in 3 phases are described by Behrendt in his work.

Loot and Destruction of the Temple

Even with the damage rendered to the temple due to the incorrect excavations and the loot conducted, the temple was still standing but unfortunately not for long. It’s fate had been sealed and it was to meet a sudden end in a manner not suitable in the slightest for a structure of such high significance. When Alfred Foucher visited the area in the same year in order to conduct further examination of what remained of the temple, he was met with a site of a great tragedy. He discovered that the entire temple had been razed to the ground by the Military Works Department and their contractors for the use of material from it for building a culvert nearby! Thus a site of such great archaeological significance met with such a mundane end at the hands of people completely apathetic to local history.

And thus a temple preserved for thousands of years could not be preserved in the face of European officers and both their appetite for acquiring artefacts and disregard for foreign history.

Though a small yet pertinent question still remains, where are the stolen pieces of the temple? Contrary to what was in the report, no part of the temple or its porch sits with the British museum or is even within its large collection of Gandharan art and artefacts!

The temple’s porch, pillars and various other parts most probably entered the lucrative artefacts business and are most probably astored in the various personal collections and auctions around the world which currently hold a great amount of Gandharan art worth millions of dollars.

This was the story of how a temple preserved for thousands of years could not be preserved in the face of European officers and both their appetite for acquiring artefacts and disregard for foreign history. Though with further investigation about the temple and a far more active archaeology department of Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, it is hoped that many such interesting sites of our history shall be discovered in the future.

References

The ”Ionic Temple” of Chakdara, Malakand, Additional notes and new data – Zarawar Khan

Alexander Caddy’s 1896 Survey of Archaeological Sites in the Swat Valley: The Chakdara Ionic Temple and other Sites – Kurt Behrendt