By Alina Izhar

Aziz Mian imploring the wealth accumulators with a dismissive disdain for almost an hour in his “Arey Daulat key banday” was a common occurrence for summer nights spent lazing around. Mian’s open throat crooning a tale of feudal injustice, repetitive clapping, and a barbed sitar made for a meditative time. I must admit, I haven’t heard Aziz Mian in a long while. The occasional live performance of qawwali is usually subjugated to repeating Nusrat’s stellar compositions, the crowd only taking the bait then. Qawwali did make a journey from Sufi shrines to a more commodified alternative of cassette tapes but it seems as if it has lost that status as well.

Qawaali in the New State

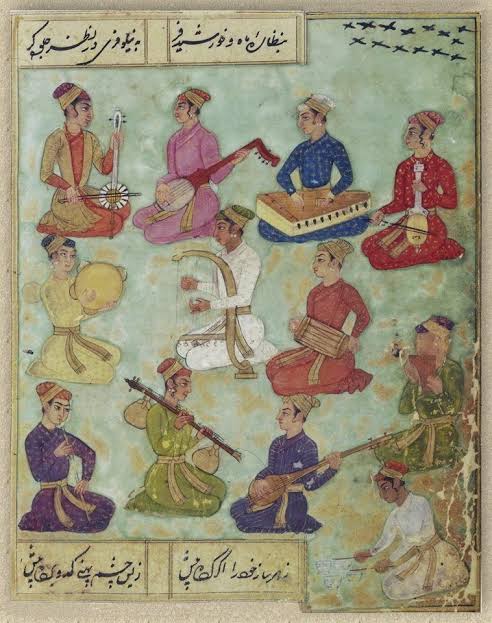

Post-partition saw Pakistan striving to build a cultural identity distinct from that of India. The diaspora’s ambivalence allowed a centralized hold over cultural identity. Classical forms such as “Khyal” and “dhrupad” were disregarded for qawwali. This was particularly easy as the Islamic mysticism of Sufi scripts was something India, in hopes of finding its own identity, wanted to distance itself from. A desperate search for a national identity, irrespective of provincialism, and the 1953 Islamic radicalistic movements made it easy for the state to start regular broadcasting of qawwali. With Ayub’s era in the late 60s and the prominence of TV among local houses in the 70s, came names such as those of Ghulam Farid Sabri, Manzur Niazi, and Bahauddin. Farid Sabri initiated the tradition of improvisation in storytelling. This became the standard due to Farid’s success but later, when qawwali experienced further commodification, the narrations were lost to limited recording time and a commercialized operation.

Qawwali at this time saw considerable state patronage due to the interest in relaying a standardized cultural congruence. Along the way the original transcendental ambiguousness found traditionally in a live performance was lost to a more concrete format that was easily digestible for the white-collar masses. A more incontestable theme and rhythmic chorus became the norm. The last of prominence in this genre was experienced by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, born into the Lasoori Shah qawwal family. Nusrat’s lineage saw a move of darbari qawwali from Ustad Mian Maula Buksh to Nusrat’s father and uncle, Ustad Fateh Ali Khan and Ustad Mubarak Ali Khan. Nusrat brought the genre into a world of cassette tapes and CDs but somehow retained the soul despite the amount of procession. But recent times have shown qawwal groups facing difficulties in increasing consumer demand which has seen a steady decline. Subhan Nizami, in Alifiyah Imani’s “Qawwal Gali: the street that never sleeps” mentions that qawwali as a genre has not been getting any state funding or support. According to him, his group experiences more appreciation on international stages rather than at home. Reliance on private gatherings, which according to Nizami are not enough, and international tours is barely keeping the genre afloat.

The influence of globalization and the homogenous mainstreaming of music has done great damage to qawwali. The monopoly of one or two record labels has centralized production in a few hands. But recent developments of Coke Studio have shown a fusion being promoted on a national level. Though one could argue, this sacrifices the roots of the genre to make it more market access. Now, qawwali tracks are constrained within 7 to 8 minutes. I often joke that it used to take 7 minutes for the qawwal to freshen up previously. This constraint and fusion of qawwali with other genres, an oversimplification of diction and literary devices compromise the soul of the genre.

Vanishing Themes and Emotions

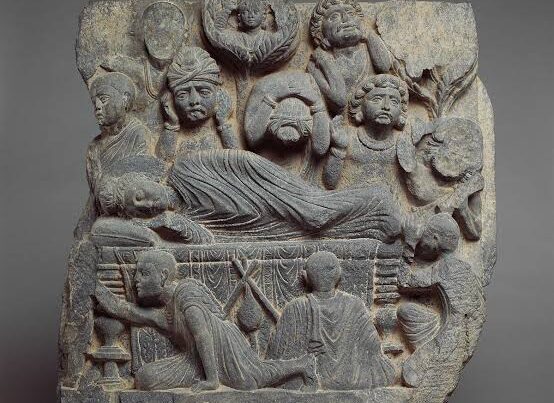

One could argue that there has been a move away from the enigmatic way of qawwali whose purpose was to leave one questioning the prescribed bounds. The recurrent themes of love and devotion, with the suffering that’ll pave the way towards Ishq-e-haqiqi , simply do not fit with the enlightenment of the 21st century. There is no room or time for mysticism and all its uncertainty. Theodor Adorno in his “Dialectic of Enlightenment” argues that the countless agencies of mass production and its culture impress standardized behavior on the individual as the only natural, decent and rational one. Individuals define themselves now only as things, statistical elements, successes, or failures. Hence, qawwali is simply not digestible anymore, it is difficult to process and has nothing to add to a system running on cost-benefit analysis. The wealthy patrons have stopped indulging as it does not fall in line with the more educated. Terrorism on shrines by Islamic militants and the general air of fear and doubt has also steered away the financially affluent clientele.

Today, qawwali nights are rampant, especially for younger audiences, but part of the experience is lost in the limited minutes, repetitive tracks, and modern amplification. The modern qawwali experience has become more of a bohemian getaway for the audience, a peculiarity that promises a good time. There is hardly any room for qawwal groups to innovate and improvise because of time constraints and the audience’s indifference as well as impatience. In a music industry only possible on promotions and marketing, modest resources hardly help the groups. The freedom to perform, to offer an alternate experience is no longer a priority. Qawwal Agha Rasheed Faridi once said that if it was up to him, his audience would leave the mehfil with their clothes in tatters. The experience of qawwali forwent bounds, constraints, it was to leave the state of hindrance put forth by societal religious expectations and truly introspect as well as learn, find. It should be clarified that I do not mean one should not listen to qawwali if they do not intend to follow through with the whole experience. That puts qawwali inside a boundary, only meant to be breached by a few. It is in fact the exact opposite of this.

A Peculiar Future

The following generation might prefer a shorter, more unambiguous style of qawwali. Consumer choices and utility have become the salient feature in this time, qawwali’s new look as a commodity already renders it a short-lived good time with friends rather than the means to your devotion. Moreover, it is slightly unfair to criticize this pop culture Sufism considering qawwali has always changed faces in different circumstances. Nadeem Farooq Paracha in “Soul Rivals: State, Militant and Pop Sufism” mentions that the late 60s saw qawwal groups performing at private gatherings held by the bureaucrats, military personnel, and the elite. These gatherings often garnered a slight swing of heads from the audience as they raised their glasses at the qawwal. Anything more than this, especially the ecstatic dhamal found at shrines, was deemed unbecoming. It would be slightly naïve to try and associate modern qawwali with its lost form. Especially considering that even before Amir Khusro, qawwali opted for various styles of various regions. There were no set rules and no one way considered as one’s appropriate reaction. Qawwali at its core is a celebration of the divine and the way to acknowledge that can be through different means.

References

Imani, Alifiyah. “Qawwal Gali: The street that never sleeps”. Herald. 22nd June, 2016.

http://herald.dawn.com/news/1153223/qawwal-gali-the-street-that-never-sleeps. Accessed

26 June 2023.

Paracha, Nadeem. “Soul Rivals: State, Militism and Pop Sufism”. New York City. Vanguard.

1st January 2020.