By Mahnoor Ikram

The feminine in Punjabi poetry

Affection, celebration of harvest, parting and banishment are some of the most noticeable and prevailing themes in Punjabi oral tradition. However, women’s archetypes in the oral tradition were usually split between the dutiful, submissive wife whose main characteristic was virtue and the heinous seductress as a risk to the family values and morality i.e in the oral tradition of Puran Bhagat. Oral traditions usually end with some kind of divine moral punishment or redemption being sought by the protagonists. The culture of the Punjab has always been thoroughly inclusive of the female gender as reflected in the works of different poets most notably Bulleh shah who not only used a female narrative but also portrayed women as other than the stereotypical archetypes that already existed. That the teachings of Islam; especially Sufism do not incorporate any gender bias, both men and women are seen in the same light when following the teachings of and striving hard for morality and ethics

Author and expert on Punjabi classics, Mushtaq Soofi highlights the fact that these character traits were usually attributed to the upper middle class women of the Punjab and not the working class majority of the agrarian women. Nevertheless, for the agrarian families of the Punjab, the qisse was an important source of literary entertainment. “Their (oppressed women in the families) role model could be none other than Hir, a confident upper class Jat woman from Jhang, who is bold, resilient and capable of standing up to patriarchy in defense of her devotion to Ranjha, the flute playing Jogi from Takht Hazara, Chenab”, says Mushtaq Soofi.

Bulleh Shah channels the feminine

Bulleh shah’s poetry often incorporates elements from the oral tradition of Heer Ranjha. The Punjabi Sufi poets time and again allude to the story in their poetry; using the archetype of the restricted lover and writing themselves into the archetype whilst referring to God as their beloved. The spectre of the Heer Ranjha story is especially vivid in the Kafia where Bulleh’s sisters-in- law and family come to persuade him to leave interaction with those of lower caste then himself. He writes “Bulla’s sisters and sisters-in-law came to him, / To make him see some sense. / “Listen to us, Bulla”, they said. / Leave the hands (company) of wanderers and wayfarers and Arains.”

“Bulleh Nu Samjhawan Aaiyaann Bhaena Tey Bharjayee-yan

Man Lay Bulleya Sada Kena, Chad Day Palla Raaiyan”

Similarly in Heer Ranjha; Ranjha has a similar answer when his brothers and sisters-in-law ask him to return to Takht Hazara. He replies, “Moments that sail past do not return; fortunes lost will not come back; a word uttered cannot be recalled; the released arrow does not revert to the bow; the escaped soul does not re-enter a dead body”

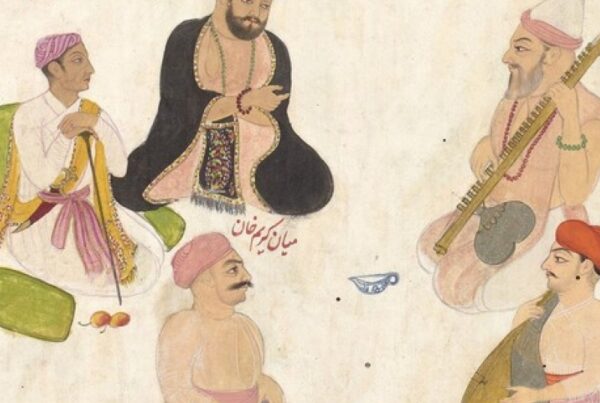

Waris Shah eloquently retells the epic in verse form; he describes the air of the Punjab the travelling holy men, the chieftains, the clan rivalries, the customs, the women spinning cloth and weaving tapestry as a feudal system weighs down upon the shoulders of the ordinary man and the life sustaining Chenab with its enlivening waters and boats and fishermen casting their nets.; arguments, feuds, speeches, declarations and declamations, urgings and quarrels between one and all characters.

The fact that Bulleh shah pays homage to Heer by describing a scene identical to the original telling, where the family tries to convince Heer to give up Ranjha, reflects undertones of Waris’s epic in Bulleh’s poetry.

Perhaps, most significant however is evidence not from Bulleh’s work but from his life. The popular Qawali “Mera piya ghar aaya” was originally said to have been penned by Bulleh. Though at first glance it appears to be a celebratory hymn of a female for her beloved returning home, it was in fact written by him upon the return of his spiritual mentor, Shah Inayat. Kriti Singh summarises this story in her article titled Bulleh Shah and Shah Inayat: Caste in 17th century Punjab. She states: “Shah Inayat came from an Arain (gardeners, vegetable-growers, considered to be a “lower”) caste. When Bulleh Shah’s family had heard that he had chosen an Arain as Shaikh, they became furious and took it upon themselves to convince Bulleh Shah to leave him and find someone “more worthy”. “How can an Arain be a teacher to a Syed?” he was asked.

Heart-broken, obligated and even a little swayed by his family’s convictions, Bulleh Shah went to Shah Inayat to declare that he would no longer be his disciple and stated his reason — the lowness and the highness, and the incompatibilities it presented. On hearing this, Shah Inayat was believed to have replied in only one line: ‘Tu Bullah nai tu bhulliyan ann’ (You are not Bulleh, you are lost)”

According to another version of the tale Shah Inayat chose to leave the village and Bulleh was left without a spiritual teacher. Disheartened and distraught, Bulleh joined a troupe of low caste travelling musicians or Kanjars. During this period he would dress in women’s clothing and dance in the streets, later penning “Tere Ishq Nachaya” for his beloved teacher. The significance of Bulleh recognising the experiences of caste and gender discrimination is later reflected in his work.

Bulleh recognises God as not only having masculine properties of wrath and power but also the feminine qualities of love, forgiveness, gentleness and creation. Indeed, in Islam God is described as loving his creations seventy times more than a mother. Verse after verse Bulleh acknowledged that it was really his mentor who had introduced him to the love of God. Henceforth, Bulleh and his master were inseparable. He says “Cow herder you are to others / you are my faith, / do come to me / Leaving my parents, I am tied to you / Oh Shah Inayat, my beloved teacher / do come to me”.

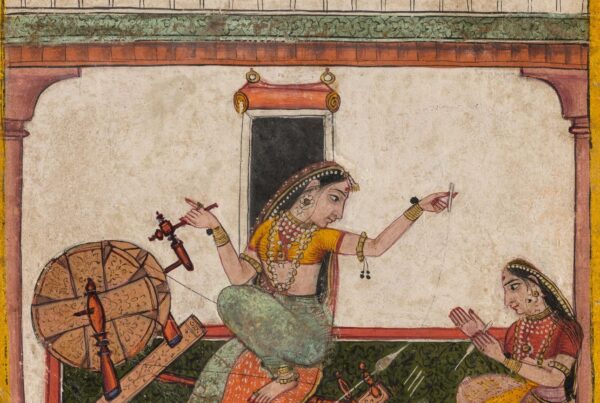

One Kafia by Bulleh shah describes the domestic oppression women faced at home. Years and years were spent in front of the spinning wheel, the furnace or by collecting cotton. This was not the condition of women only in the subcontinent but all over the world. The Arabs pre-Islam were staunch believers in daughters being accursed while the Greek statesman Pericles once commented that the more inconspicuous women were the better. Gender roles in ancient and medieval civilizations were restrictive and deterring.At such a time for Bulleh to talk of the chores and tools of women was almost radical. He says “It is good that my spinning wheel has broken / My life has been relieved of a burden”. He further says “I have become defeated picking flowers, / The owner of which is the cruel landowner.”

“Bhalla hoya mera Chrakha tutiya

Meri Jind azaabaun chute”

“Mein kasambra chun chun haaree

Ays Kasambray de kunday bhuleray ur ur chunri paree

Ays kasambray da hakim karra zalim ay patwari

Mein kasambra chun chun haari”

In the verses above Bulleh not only channels and conveys the thoughts of an oppressed female, but also hints at a greater hierarchy of coercion. By using certain terms and allusions to portray love Bulleh projects himself as a female lover and displays the emotions, aspirations and the restrictions of a gender that was usually not cited or mentioned. In this way Bulleh provides a unique insight into the lives of women at the time the works were composed.

Conclusion

It seems that even though contemporary western singers might push certain female narratives as empowered onto the subcontinent, Bulleh was one poet who always recognised the female as a noteworthy individual with a voice.

An insightful analysis. Would love to see more on mystical poets of the subcontinent. Prayers to you.